Let them all break down

Sometime in June 2022, every parking meter in Providence, Rhode Island fell offline. Up until then, the city had used the omnivorous single-space meters that accept both coins and cards. Overnight, they went retro. Quarters only, please.

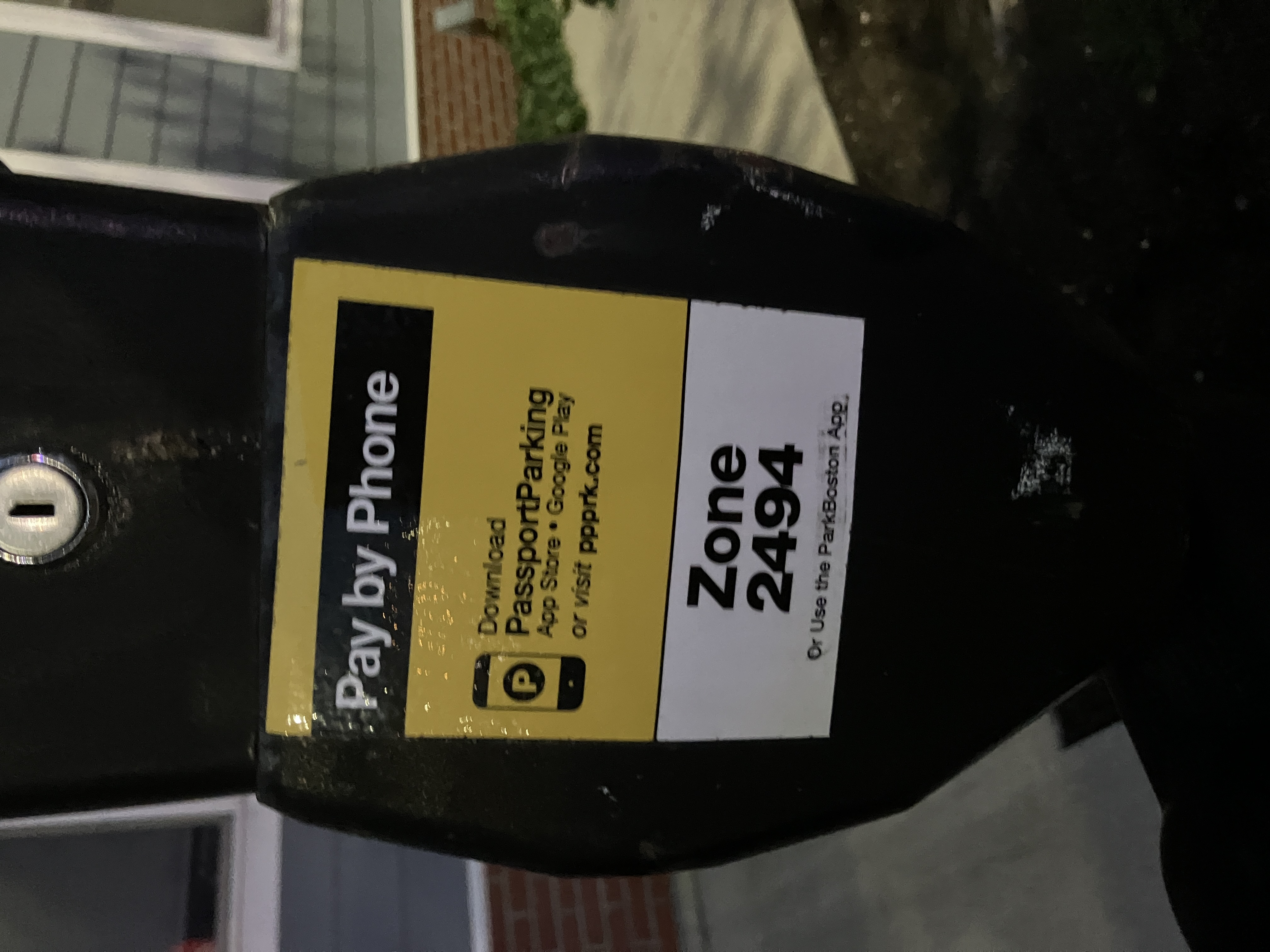

Unfortunately the blackout didn’t come with the joy of a meter jam (“I guess we don’t have to pay!”). Instead, black-and-orange stickers told us we could send our $0.75 through the city’s app.

Government tech, things like parking meters, seem to break all the time. Usually the fault lies near the nexus of human error and bureaucratic sadomasochism. This time, though, things were a little different. The meters had used the 3G network, and in 2022, 3G was in the process of being decommissioned. Without access to their home spectrum, the meters’ delicate Internet of Things collapsed.

The first time I was caught quarterless downtown, I don’t think I had thought about 3G in years. I didn’t know it was being sunset, hadn’t thought that something like that “could be done.” But, technically, it makes sense. The wireless spectrum has a limited range of frequencies, and 3G is a terrific spectrum hog.

It’s not that simple though, because a lot still depends on 3G. At the time of the spectrum shutdown, a wireless trade group estimated that about 9% of digital devices were still using the 2G and 3G networks. Some of these were earlier cell phones, but some are closer to parking meter land: medical monitors, home alarm systems, OnStar. There's no frontwards compatibility: losing 3G access simply makes them obsolete.

The 3G shutdown continues to impact people in rural areas, where older networks might be the the only option for cell service. A few small providers still run 3G networks, but the big monopolies like Verizon and AT&T have simply closed up shop. These are the same companies that, for years, have refused to upgrade rural networks to 4G and 5G, even when they receive huge government subsidies to do exactly that.

Dig if you will, a Top 30 Innovative Brand of the Year

But, for now, turning back to the meters, where the disappearance of 3G IoT has created a market opportunity for “smart city” firms and a freakish hassle for the rest of us. In the last newsletter, Ken shared a link to a blog post by Gravis about the bug-ridden, exploitative world of pay-by-phone parking. It’s titled “hahaha we live in hell,” just to give you an idea.

If there’s an app-based parking system that’s half as easy as a coin slot, I haven’t met it yet. Regardless, parking app providers have signed contracts with hundreds of cities, and honestly, it’s a pretty smooth grift. They’re moving the computation power over to people’s smartphones, and getting paid to do it (Why Does Abu Dhabi Own All of Chicago's Parking Meters? ROI).

Companies like Passport and ParkMobile say their apps are more than meters—they conduct “parking policy management.” But really, they just remind me that most “smart” tech we encounter as citizens doesn’t seem to make our lives much better. Instead, it makes it easier for the rules to change without notice, and harder to screw up once in a while without getting slapped with a fine.

City enforcement is already unequal. Just one example: a study by Noli Brazil found that in Los Angeles, parking tickets were handed out more frequently in neighborhoods with higher numbers of Black, young adult, and renting residents. Automated enforcement, broken apps and smartphone requirements can only make this worse.

I think, broadly speaking, we need things to fail, and they ought to fail in our favor some of the time. Maybe I’m saying this because I’m sometimes a bad citizen, but I also think it’s just true: let the ticket get lost, let the vending machine push out two Pop-Tarts, let the meter break.

Member discussion